The Tapajós River is wide and quiet at dawn, the kind of stillness that makes you aware of your own breath. Mist rises from the water in slow spirals as the forest wakes – a forest that, as we would learn again and again, is not just a biome, but a civilisation.

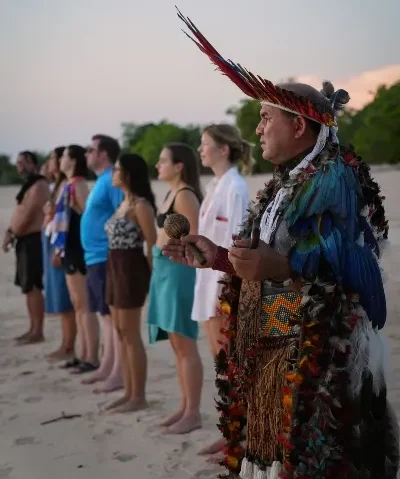

Our journey was hosted by Brazilian travel specialists, Umacanoa, and Kaiara, a community-rooted expedition organisation working along the Tapajós and Arapiuns rivers. It unfolded as a lesson in what the Amazon really is when you step away from the narratives written far from here. This was not a trip defined by the comfort of a boat or the remoteness of the forest; it was defined by the people who live inside this ecosystem and the quiet, determined guardianship they practice every day.

Jamaraquá: Where the forest’s memory lives in people

Our first day was spent with the community of Jamaraquá, set within over 500,000 hectares of the Tapajós National Forest – a mosaic of 17 communities, three of which are Indigenous. From the moment we stepped onto the trail, our guide challenged us to do something simple but radical: to question everything we thought we knew about the Amazon.

Here, the global headlines about fires and gold rushes become intimately local. Declining fish stocks and fruit harvests tell the story of mercury contamination. Soy and cattle industries press in from all sides. The community is surrounded – geographically, politically, economically – yet deeply rooted.

We followed a path shaded by a 150-year-old piquia tree, its seeds used as natural medicine for generations. Nearby stood another tree between 200 and 250 years old, a species prized for furniture. When we asked its age, our guide smiled gently: “Everything has a cycle. A tree lives as long as the soil stays alive.”

It was a reminder that the forest is measured not in years, but in reciprocity.

As he spoke about conservation, his voice thickened with emotion. He told us about his uncle, who once cut trees to survive; about the years when young people left to seek income elsewhere; and about how tourism has kept them home. Since 2002, community-based tourism has offered a livelihood rooted not in extraction, but in stewardship. Today, families make natural latex jewellery, harvest cacao, and teach visitors about the living forest that sustains them.

Walking deeper into the trail, he spoke of his ancestors – skilled agriculturalists who created terra preta, engineered landscapes, and established thriving settlements across the Amazon. “People say the Amazon is empty,” he said. “But under the forest, there are other forests – the forests made by people.”

It reframed everything. The Amazon is not wilderness untouched; it is a cultural ecosystem shaped by thousands of years of human knowledge.

Travessia Anã-Maripá: Seeing the forest through the people who hold it

The next day, we travelled by river to communities within the Tapajós-Arapiuns Extractive Reserve, a place where community-led tourism, agroforestry, and grassroots advocacy coexist with profound systemic challenges.

Our guide, Maria, welcomed us with a simple statement that carried the weight of a manifesto:

“People look at the Amazon and see only nature. But we are here. We are the forest.”

Kaiara supports a project here that brings young people from across Brazil to learn directly from these communities. Many arrive believing the forest is empty; most leave transformed by the depth of what they encounter.

In one village of 114 people, we met leaders working towards a zero-plastic future. They burn waste because no municipal system exists – a reality faced by many remote communities across the Amazon. Yet they are piloting a partnership with a Brazilian-French NGO to press plastic for safe transport to Santarém. Glass and batteries remain unsolved challenges, but the effort is ongoing, driven by women imagining a future where waste no longer litters their forest.

Advocacy here is not metaphorical. It’s survival. Agro-industry interests are powerful and prefer communities disempowered. For four years, local leaders fought for specialised healthcare; only now, with support from a coalition of NGOs, does a medical boat visit regularly. “Better to be inside the system,” they said, “because outside, we are attacked.”

Sitting beneath the shade of trees, listening to the community talk about waste solutions and climate, we felt something profoundly hopeful: the Amazon’s future is being shaped by its people, not for them.

Between River and Forest: A Living, Breathing Classroom

Moving along the Tapajós by boat, paddling through flooded forests, walking on dry trails where canoes drift in high-water months, the journey underscored a simple truth: seasonality is the Amazon’s heartbeat. Kaiara never overpromises activities; instead, they invite travellers to follow the rhythms of the forest, not impose their own.

Guides spoke about flying rivers, the vast invisible water systems that carry Amazonian moisture south to fuel Brazil’s agriculture. Cut the forest, they said, and the country loses its rain.

Over and over, the narrative shifted from the Amazon as a pristine wilderness to the Amazon as a contested, living, human ecosystem, one whose future depends on defending the rights and dignity of the communities who protect it.

Reflections for JWP: Why Encounters Like These Matter

Travelling with Kaiara revealed a powerful intersection of culture, ecology and community agency – precisely where JWP’s mission sits.

This journey deepened our belief that impact travel must centre the people who guard the world’s most vital ecosystems. The Tapajós is not a place to simply observe; it is a place to learn from those who have safeguarded its abundance for centuries and continue to do so under extraordinary pressure.

For JWP, this experience reinforces several convictions:

Access leads to understanding. Being welcomed by communities challenging extraction and building their own futures offers a perspective no report or documentary can replicate.

Knowledge is responsibility. Learning about mercury pollution, flying rivers, terra preta, cultural continuity, and political vulnerability demands that we engage more thoughtfully with the Amazon’s narrative.

Connection inspires action. The conversations we had – emotional, generous, urgent – are the kind that turn travellers into long-term allies.

The Amazon’s challenges are immense, and yet the hope we found along the Tapajós was grounded, practical, lived. Communities here are not waiting to be saved; they are leading. Our role is to listen, learn, and support the pathways they determine.

As the river carried us onward each evening, the forest glowing in the late light, it felt clear: To travel with purpose in the Amazon is to witness resilience – and to understand our place within it.